Grizzlies in the Gravellys

Two bear attacks in the same area, on the same day

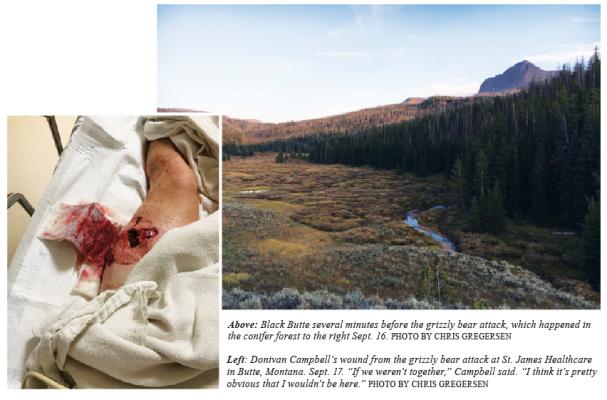

Donivan Campbell wrapped his hands around the back of his head and neck as a grizzly bear pinned him face down in a forest west of Black Butte, the highest peak of the Gravelly Mountains. He felt the moist warmth of the bear’s mouth on the hand covering his head as a large tooth slid between his fingers. At the same moment, his hunting partner shot at the grizzly from behind, jolting the bear into the nearby brush.

When Chris Gregersen got to his friend seconds later, the bushes shook, and the ground cracked under the weight of the bear charging the bow-hunters again.

The end of summer in the Greater Yellowstone area aligns with the beginning of bow-hunting season. Cooler temperatures alert all of the incoming winter, especially bears preparing for hibernation.

“They have this hunger to consume, that in itself makes it more likely for them to be aggressive,” Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks Region 3 Information and Education Manager, Morgan Jacobsen said.

Campbell and Gregersen met at Washington State University in their field of study, wildlife biology. Over shared interests in the outdoors, they became quick friends. They have hunted together all over the West, but this was their first time in Montana.

Nearly 12 hours prior, a grizzly bear attacked two different bow-hunters on the same north-facing slope near Cottonwood Creek in the western Gravelly Mountains.

According to FWP, the hunters from New Mexico were walking south from Cottonwood Creek, when a grizzly bear attacked them. As one of the hunters reached for the bear spray around his waist, the bear struck him to his hands and knees and grabbed onto his backpack.

The other hunter deployed his bear spray causing the bear to attack him. He continued to spray the bear and it eventually left.

They drove to Madison Valley Medical Center in Ennis, where they were treated for moderate injuries and released later that day.

After the second attack, Cottonwood Creek Road was closed and FWP wardens and Forest Service law enforcement began investigating the area.

“Hunters are, by nature, going against what we advocate to being bear aware,” Jacobsen said. “And are more likely to surprise a bear at close encounter because they’re being quiet, wearing scent control and wearing camouflage.”

Grizzly bear encounters in the Northern Rockies have been on the rise over the last several decades, partially due populations growing and expanding.

When grizzly bears were listed as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act in 1975, as few as 136 grizzlies were estimated to be in Greater Yellowstone. Today, there are more than 650 Yellowstone grizzlies occupying 48 percent more of their Greater Yellowstone habitat than in 1975, according to the International Grizzly Bear Committee.

Grizzly bear distributions in the Greater Yellowstone and the Northern Continental Divide zones have expanded beyond zone-boundaries, and into more human populated areas in Montana and Wyoming, according to U.S. Fish & Wildlife Services. An estimated 1,029 grizzlies are in the Northern Continental Divide population, according to International Grizzly Bear Committee.

“Grizzly bears in the Gravelly Mountains are a prime example of them passing their recovery zones,” Jacobsen said.

The Gravellys’ rolling peaks set them apart from the jagged mountain ranges that surround them. Residents and visitors recreate year-round in the subalpine meadows and conifer forests that roll out into the Madison and Ruby Valleys.

Campbell and Gregersen left their wall tent along Cottonwood Creek road for the second time on Sept.16. They hunted separately that morning, but left together for the afternoon hunt around 3:30 p.m.

They drove up Cottonwood Creek Road about four miles from their camp site and parked. Sliding their packs over their shoulders and situating their compound bows, they didn’t say much. It was the third day of their two-week hunting trip in Montana.

After a few hours, Campbell and Gregersen started walking back toward the truck, when they found elk tracks going in the same direction. The afternoon light softened as they followed the tracks down a north facing slope.

A crashing sound broke the silence and a grizzly bear emerged out of the brush about 20 yards to their left, charging at full speed. Gregersen yelled, “BEAR,” and threw himself down the hill as it charged toward him with its mouth open and breathing hard.

“It was just like a shot out of a cannon toward us,” Gregersen said. “There was nothing you could do about it except try and get out of its path, but that was a second. You could have been holding bear spray in your hands and it wouldn’t of been enough time.”

Campbell turned right and took a couple of steps to get out of the way. As he looked over his shoulder, the bear was nearly on him. It had turned to Campbell the second Gregersen lunged downhill, and then Campbell tripped and fell face down.

The bear bit into Campbell’s left thigh, flipping him over. Campbell saw his leg in the bear’s mouth. The bear moaned and grunted as it tugged at Campbells leg. His pants and flesh ripped in its jaws.

“Before I looked up, I could hear him screaming and I knew the bear had him,” Gregersen said. “By the sound of the screams, I wasn’t sure if he was going to be alive when I got to him.”

Gregersen fell when he landed downhill and turned to see Campbell with the bear on top of him through some bushes. As he got to his feet, Gregersen pulled his semi-automatic 9 mm pistol from its holster and ran up the hill toward them.

The grizzly bear let go of Campbell’s leg, giving him a second to flip onto his stomach and cover his head. Seconds later, Gregersen was about 15 feet way, when he had the first clear shot at the bear.

“I could just see the bear facing away from me and on top of him, kind of pushing him into the ground, trying to bite,” Gregersen said. “I just took a shot as fast as I could.”

The bear disappeared into brush, then turned around. Campbell rotated on his back and pulled his pistol. They heard the bear’s heavy breathing through the thick brush as it charged toward them again.

Campbell fired multiple times into the brush as they both screamed as loud as they could at it. The bear stopped, retreated and charged a third time. Campbell shot again into the brush and they listened to the grizzly bear slowly walk away until it was out of ear shot.

“I knew he got me good,” Campbell said. “I could feel the crunch, so I knew that it was bad.”

The entire attack played out in a matter of seconds. But they were about a half a mile from the truck and an hour from the nearest hospital.

Using trekking poles and adrenaline, Campbell made it down the steep hill covered in fallen timber and across Cottonwood Creek.

“Moving about as fast as if both your shoes are tied together,” Gregersen said.

The last stretch to their truck was a sage brush hillside that rose about a quarter of a mile, but Campbell couldn’t walk anymore. Understanding the distance that they still had to travel for medical treatment, but not the extent of the injury, they decided to split up.

“I knew I couldn’t get up there,” Campbell said. “That was it for me.”

Gregersen went to get the four wheeler at the campsite, while Campbell waited on the open hillside in the fading day light.

A tourniquet, made from game bags and Gregersen’s ripped shirt, wrapped around Campbell’s leg. Any movement was excruciating.

“I knew he [the bear] was coming out, “Campbell said. “I thought he was following us the whole time.”

Campbell thought about surviving during the 20 to 30 minutes he waited for Gregersen to return. He thought about his wife, Megan, seven-months pregnant with their first child in Pullman, Washington. He thought about every noise he heard around him and in his head.

Finally, Gregersen returned with the four wheeler.

Someone at the campsite hurried to a nearby cabin to call 911 from a landline. Gregersen and Campbell started driving toward the Ruby Valley Medical Center in Sheridan. The ambulance met them past the Ruby Reservoir.

Campbell was transferred to St. James Healthcare in Butte, where he had two surgeries and was released four days later. A skin graft and at least one more surgery will have to be done.

Cottonwood Creek Road remains closed and FWP wardens and Forest Service law enforcement conducted two extensive ground searches and a helicopter search but did not locate any bears.

The mauling site was confirmed with the locating of Campbell’s and Gregersen’s belongings. But weather muddied the investigation and as time passes, it grows less likely that they’ll be able to confirm a grizzly bear.

It is unclear if the same bear was involved in both of the attacks, according to FWP.

Campbell and Gregersen are experienced hunters and outdoorsmen. As wildlife biologists, they are trained to notice certain indicators of wildlife. Their knowledge and preparedness to recreate in bear country contributed to their survival, but not nearly as much as hunting with a partner did.

Hunting with a partner was crucial for the survival in both bear attacks in the Gravelly Mountains on Sept. 16.

“That’s really what saved us, hunting together” Gregersen said. “ because it was a 50/50 chance of what person it went for and that alone gives the other person enough time to fight back.